Adolf Hitler (April 20, 1889 – April 30, 1945, standard German pronunciation [ˈaː.dɔlf ˈhɪt.ləɐ] in the IPA) was the Führer (leader) of the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nazi Party) and of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945. In that capacity he was Chancellor of Germany, head of government, and head of state, an absolute dictator.

A highly animated and charismatic orator, Hitler is regarded as one of the most significant leaders in World history. The military-industrial complex he fostered pulled Germany out of the post-World War I economic crisis and, at its height, controlled the greater part of Europe.

Hitler’s attempt to create a Greater Germany (Grossdeutschland), specifically the annexation of Austria (Anschluss) and the invasions of Czechoslovakia and Poland, was one of the primary factors leading to the outbreak of World War II in 1939. The embrace of total war both by the Axis and Allied powers during this time led to the destruction of much of Europe. Hitler is almost universally held responsible for the racial policy of Nazi Germany, the Holocaust, and the death and displacement of millions occurring during his leadership. Though he had hoped to be the founder of a thousand-year Reich, he was reported to have committed suicide in his bunker beneath Berlin with much of Europe, and especially Germany, in ruins around him and the Red Army closing in.

Adolf Hitler’s Childhood

Adolf Hitler’s early life, marked by modest beginnings, familial tensions, and personal setbacks, played a crucial role in shaping the ideologies and ambitions of one of history’s most infamous figures. Born at 18:30 LMT on April 20, 1889, in the small Austrian town of Braunau-am-Inn, close to the German border, Hitler’s upbringing in the fading Austro-Hungarian Empire would later fuel his aspirations for nationalistic and territorial expansion.

Family Background

Adolf’s father, Alois Hitler (1837–1903), was a minor customs official with a complex background. Born out of wedlock, Alois initially bore his mother’s surname, Schicklgruber, a fact that Adolf’s political adversaries would later use to taunt him. It wasn’t until Alois was 40 that he adopted the surname of his adoptive father, changing it from the original spelling ‘Hiedler’ to ‘Hitler,’ a decision shrouded in bureaucratic and personal ambiguity that Adolf’s detractors suggested hid a more ignoble ancestry.

Rumors persisted that Adolf Hitler might have had Jewish ancestry, stemming from allegations that his grandmother, Maria Schicklgruber, had been impregnated while working in a Jewish household in Graz, Austria. This speculation, however, has been largely debunked by historians such as Werner Maser and Ian Kershaw, who cite the historical expulsion of Jews from Graz in the 15th century, which would have made such an encounter unlikely if not impossible.

Adolf’s mother, Klara Hitler (née Pölzl), was Alois’s second cousin, requiring a papal dispensation for the couple to marry due to their close kinship. Klara gave birth to six children, of whom only Adolf and his younger sister Paula reached adulthood, highlighting the harsh realities of early 20th-century life that included high infant mortality rates.

Childhood and Education

From an early age, Adolf was recognized as an intelligent yet rebellious child, struggling to align his artistic aspirations with his father’s pragmatic expectations. Despite his intellectual capabilities, he twice failed the admission examinations for high school in Linz, a failure that did little to dampen his burgeoning interest in German nationalism, fueled in part by the pan-Germanist lectures of Professor Leopold Poetsch.

The death of his father in January 1903 and his mother in December 1907 to breast cancer left a profound impact on Hitler. The loss of his mother, to whom he was deeply attached, contrasted sharply with his complex relationship with his father, a strict disciplinarian who had envisioned a career in the civil service for his son. These early life experiences, marred by loss, opposition, and a sense of displacement, contributed to the formation of Hitler’s ideology, characterized by a mix of fervent nationalism, racial purity theories, and a disdain for democracy, which would later be codified in his manifesto, “Mein Kampf” (My Struggle).

Adolf Hitler’s formative years, thus, provide critical insights into the psychological and ideological underpinnings of a man whose legacy is indelibly linked with the atrocities of the Second World War and the Holocaust. The interplay of his early familial relations, personal ambitions, and the socio-political environment of Austria-Hungary set the stage for his rise to power, marking a trajectory that would lead to unprecedented global conflict and human suffering.

Adolf Hitler’s early adulthood

Adolf Hitler’s journey into early adulthood is a pivotal chapter that saw a young man with aspirations of becoming an artist evolve into a figure whose ideologies would shape the course of world history. After the death of his mother in December 1907, an 18-year-old Hitler left Linz for Vienna, fueled by dreams of artistic success. Despite his initial financial support from an orphan’s pension and later an inheritance from an aunt, Hitler found himself rejected twice by the Vienna Academy of Art. His financial resources dwindling, Hitler eventually lost his pension in 1910, and the inheritance from his aunt soon ran out as well.

Struggle and Ideological Formation in Vienna

In Vienna, Hitler’s life took a turn towards precarious living; he resided in hostels for the homeless and eked out a living as a painter, reproducing scenes from postcards to sell to merchants. Despite his marginal existence, Hitler found solace in the operas of Richard Wagner, particularly those rooted in Norse mythology, and spent considerable time immersed in reading. This period marked the beginning of Hitler’s transformation into an ardent anti-Semite, influenced by the prevalent disdain for Jews in Vienna and the deeply ingrained anti-Semitism of the Austrian Catholic culture of his upbringing.

Vienna, with its significant Jewish population, including many Orthodox Jews from Eastern Europe, became the backdrop against which Hitler’s racial ideologies began to crystallize. Influenced by figures like Lanz von Liebenfels, Karl Lueger, and Georg Ritter von Schönerer, Hitler adopted the belief in the superiority of the “Aryan race” and saw Jews as both the natural enemies of Aryans and the scapegoats for Germany’s economic woes.

Military Service and World War I

In a bid to evade military service in the Austro-Hungarian army, Hitler relocated to Munich in 1913, drawn by the city’s more racially homogenous German population. However, his avoidance was short-lived as he was arrested and deemed unfit for service after a physical examination by the Austrian army. This allowed him to return to Munich, but the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 saw Hitler eagerly enlist in the Bavarian Army. Serving as a messenger on the front lines in France and Belgium, Hitler was exposed to significant danger yet remained undaunted, his patriotism for Germany intensifying despite not holding German citizenship until 1932.

His military record during the war was noted for bravery, earning him the Iron Cross, Second Class, in December 1915, and the rare honor of the Iron Cross, First Class, in August 1918, a commendation seldom awarded to someone of corporal rank. Rumors of a psychiatric evaluation described him as “incompetent to command people” and “dangerously psychotic,” yet these did not deter his military engagement or his burgeoning nationalism.

The end of the war and Germany’s capitulation in November 1918 devastated Hitler. While recovering from a poison gas attack in a field hospital, which temporarily blinded him, he was appalled by the surrender, especially given the widespread German belief that their army remained undefeated. Hitler, along with many German nationalists, harbored deep resentment towards the civilian politicians labeled as the “November criminals” for their perceived betrayal.

Hitler’s early adulthood, marred by personal failures, ideological radicalization, and war-time service, laid the foundational beliefs and experiences that would fuel his rise to power. His narrative from a struggling artist to a passionate German patriot encapsulates the complex interplay of personal ambition, nationalist fervor, and racial ideologies that would define his political career.

The Nazi Party

Adolf Hitler’s involvement with the Nazi Party commenced in a tumultuous period following World War I, during which Germany was engulfed in social and political upheaval. Post-war, Hitler remained in the military, now primarily tasked with quelling socialist revolts across the nation, including Munich, where he would return in 1919. Amidst this backdrop, Hitler partook in “national thinking” courses led by the Bavarian Reichswehr Group’s Education and Propaganda Department. These courses aimed to find scapegoats for the war and Germany’s defeat, pinpointing “international Jewry,” communists, and a broad spectrum of politicians as culprits.

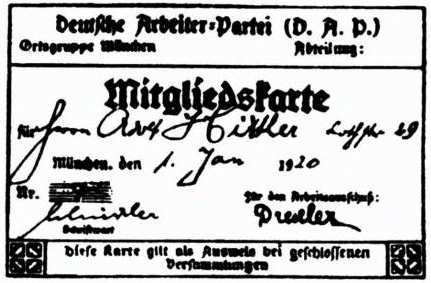

In July of that year, Hitler was assigned by the military to infiltrate the German Workers’ Party due to his notable intelligence and oratory prowess. He officially joined the party in September 1919, encountering influential figures like Dietrich Eckart, a vehement anti-Semite. By 1920, after being discharged from the army, Hitler fully immersed himself in the party’s activities, soon taking its helm and renaming it the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP), commonly known as the Nazi Party.

Hitler’s exceptional oratory skills and ability to engender personal loyalty became evident as he began to attract a following. His rhetoric, laden with attacks on Jews, socialists, liberals, capitalists, and Communists, garnered the support of early followers like Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, and Ernst Röhm, the latter leading the Nazis’ paramilitary wing, the SA. Another prominent admirer was Field-Marshal Erich Ludendorff, whom Hitler intended to use as a figurehead in an attempted coup, the “Hitler Putsch” of November 8, 1923, aimed at overthrowing Bavaria’s government and marching on Berlin. The putsch failed, leading to Hitler’s arrest and subsequent trial for high treason. Sentenced to five years in Landsberg prison, Hitler was released early, having served less than a year. During his incarceration, he dictated Mein Kampf to his deputy, Rudolf Hess.

Upon his release, Hitler faced the daunting task of revitalizing the nearly defunct Nazi Party. He established the Schutzstaffel (SS), a personal bodyguard commanded by Heinrich Himmler, which would later play a central role in executing Hitler’s plans regarding the “Jewish Question” during World War II. Hitler’s rhetoric capitalized on national disgruntlement with the Treaty of Versailles, which imposed harsh terms on Germany. Despite early challenges in gaining widespread support, the Nazi Party’s refined propaganda, blending anti-Semitism with criticism of the Weimar Republic and its supporters, began to resonate more broadly with the electorate.

An intriguing aspect of Hitler’s history emerged in 2004, revealing his years of tax evasion, during which he accumulated a significant debt to German authorities. By the time he rose to power and his debts were absolved, Hitler owed the equivalent of 8 million US dollars in 2004 currency. This detail adds a complex layer to the understanding of Hitler’s early political maneuverings and his rise within the Nazi Party.

The Road to Power

Adolf Hitler’s ascendancy to power was a complex process, fueled by Germany’s socio-political turmoil and economic hardships. The period following World War I was marked by widespread unrest and the rise of various political movements, setting the stage for Hitler’s eventual domination of German politics.

The Post-War Environment and Hitler’s Early Political Involvement

After World War I, Hitler remained in the army, which was now primarily focused on quelling socialist uprisings across Germany, including in Munich where Hitler had returned. He participated in “national thinking” courses under Captain Mayr at the Bavarian Reichswehr Group, which aimed to find scapegoats for World War I and Germany’s defeat. “International Jewry,” communists, and politicians were blamed, aligning with Hitler’s developing anti-Semitic and nationalist views.

In July 1919, Hitler’s oratory and intelligence led to his recruitment into the Bavarian Reichswehr’s “Enlightenment Commando” to influence soldiers and infiltrate the German Workers’ Party (DAP). By September 1919, Hitler joined the DAP, meeting key figures like Dietrich Eckart. His involvement grew, and by 1920, after being discharged from the army, Hitler became the party’s leader, transforming it into the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP or Nazi Party).

The Path to Power

Hitler’s exceptional oratory skills and ability to inspire loyalty became evident. Early supporters included Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, and Ernst Röhm. The “Hitler Putsch” in November 1923 was a failed coup attempt, leading to Hitler’s imprisonment, where he dictated “Mein Kampf.” His release in December 1924 marked a period of rebuilding the Nazi Party, culminating in the establishment of the SS under Heinrich Himmler.

The Treaty of Versailles’s harsh terms fueled national resentment, which Hitler exploited, blaming “international Jewry” for Germany’s humiliations. However, it was the Great Depression that catalyzed the Nazi Party’s surge, winning 18% of the vote in the 1930 elections.

Hitler’s Rise to Chancellor and Consolidation of Power

Hitler’s appeal to German farmers, war veterans, and the middle class, disillusioned by inflation and unemployment, propelled the Nazis to become the Reichstag’s largest party by July 1932. Despite initial setbacks and the loss of some support by November 1932, negotiations and political maneuvering led President Paul von Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Chancellor on January 30, 1933.

The March 1933 elections saw the Nazis winning 44% of the vote, and the subsequent passage of the Enabling Act granted Hitler dictatorial powers. The Act allowed Hitler’s cabinet to pass legislation, effectively sidelining the Reichstag and marking the beginning of authoritarian rule. The consolidation of power was complete with the merging of the Chancellor and President roles after Hindenburg’s death in August 1934, with Hitler assuming the title of “Leader and National Chancellor.”

This period saw the suppression of all opposition, the banning of other political parties, and the military swearing an oath of allegiance to Hitler personally. Adolf Hitler’s road to power, from a political agitator in the post-war years to the undisputed leader of Germany, was marked by strategic opportunism, exploitation of national grievances, and ruthless suppression of dissent, setting the stage for the atrocities of the Nazi regime and World War II.

The Nazi regime

Adolf Hitler’s rise to power and the subsequent Nazi regime’s impact on Germany and the world is a multifaceted narrative encompassing political manipulation, economic revival, cultural transformation, and unprecedented atrocity. Hitler’s ascent was initially marked by his ability to secure supreme political power in Germany without a majority support, leveraging his oratory skills and the control of mass media by his propaganda chief, Dr. Joseph Goebbels. Through persuasive messaging, Hitler positioned himself as Germany’s savior from economic depression, perceived communist threats, the Treaty of Versailles, and anti-Semitic scapegoating of Jews.

Economic and Cultural Revival

Under Hitler’s rule, Germany witnessed one of its most significant expansions of industrial production and civil improvement. Achieving near full employment, the regime expanded Germany’s economic and industrial base and launched a vast infrastructure campaign, including the construction of dams, autobahns, and railroads. These initiatives, coupled with health programs for ethnic Germans and an emphasis on traditional family values, bolstered Hitler’s popularity. The regime also promoted architectural and cultural excellence, with Berlin’s hosting of the 1936 Summer Olympics serving as a global showcase of German prowess.

Repression and Consolidation of Power

However, this facade of prosperity and cultural renaissance was underpinned by brutal repression. The SA, SS, and Gestapo enforced Hitler’s rule, targeting political opponents, Jews, and other minorities. The Night of the Long Knives in 1934 saw the purging of Ernst Röhm and other perceived threats, solidifying Hitler’s control. Following President Hindenburg’s death, Hitler merged the presidency and chancellorship, demanding personal loyalty from the military, effectively becoming the unchallenged Führer of Germany.

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 institutionalized racial discrimination against Jews, progressively isolating and disenfranchising them from German society. The intensification of anti-Jewish policies culminated in the Kristallnacht pogrom of 1938, further tightening restrictions and leading to the mass emigration of Jews from Germany, who left behind seized properties.

Military Expansion and Alliances

Defying the Treaty of Versailles, Hitler initiated Germany’s rearmament, introducing conscription and building a formidable military force. The remilitarization of the Rhineland in 1936, the intervention in the Spanish Civil War, and the formation of the Axis Powers with Italy, Japan, and other nations exemplified Hitler’s aggressive foreign policy and expansionist ambitions.

The Holocaust

The gravest legacy of Hitler’s regime is the Holocaust, the systematic, state-sponsored genocide of six million Jews, along with millions of others deemed undesirable by the Nazi ideology. Between 1942 and 1945, the SS, with support from various collaborators, executed a plan of mass murder primarily through concentration camps. This genocide also targeted political dissidents, homosexuals, disabled individuals, Roma, and others, marking one of history’s darkest chapters. The planning and execution of the Holocaust, including the pivotal Wannsee Conference, underscored the regime’s commitment to the “Final Solution” of the Jewish question, a policy endorsed at the highest levels of Nazi leadership, including Hitler himself.

Hitler’s regime, characterized by its initial economic revival, cultural initiatives, and infrastructural projects, is indelibly marred by its foundational pillars of hate, aggressive militarism, and the unspeakable horrors of the Holocaust.

World War II

Opening Moves

World War II began with a series of aggressive moves by Adolf Hitler, leading to a conflict that would engulf the globe. Initially, Hitler’s annexation of Austria in March 1938 and his demands on Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland, which culminated in the Munich Agreement, signaled his aggressive intentions. This agreement, seen by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain as ensuring “Peace in our time,” ironically emboldened Hitler further, earning him Time Magazine’s Man of the Year in 1938 for his influence on global events.

The situation escalated in March 1939 when Hitler seized Prague, leading Britain and France to oppose further territorial demands, particularly concerning Poland. The failure of Britain and France to secure an alliance with the Soviet Union against Germany allowed Hitler to outmaneuver them by signing the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with Stalin in August 1939. This secret alliance paved the way for the invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, prompting Britain and France to declare war on Germany.

Following the rapid conquest of Poland, Hitler turned his sights westward, launching successful invasions of Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France in 1940. Italy, under Benito Mussolini, joined the Axis powers, drawn by Hitler’s string of victories. However, Britain, having evacuated its forces from Dunkirk, continued to resist, enduring the Battle of Britain and preventing a German invasion.

Path of Defeat

The tide of war began to turn with Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s ambitious but ultimately ill-fated invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Despite early successes, the German advance was halted by the harsh winter and staunch Soviet resistance, particularly at the Battle of Moscow.

The path to defeat for Germany began with significant losses, such as the Battle of Stalingrad and the defeat in North Africa at El Alamein, highlighting strategic missteps and the decline of Hitler’s health, possibly due to Parkinson’s disease. Hitler’s decision to declare war on the United States further tilted the scales against Germany, aligning the industrial and military might of the US, the British Empire, and the Soviet Union against him.

The overthrow of Mussolini in 1943, the successful D-Day landings by Allied forces in 1944, and the subsequent push towards Germany from both east and west signaled the impending defeat of Nazi Germany. Despite attempts by some German officers to remove Hitler from power, such as the July 20 Plot, Hitler remained in control until the end.

Defeat and death

By late 1944, the Soviets were reclaiming territory and pushing into Central Europe, while the Western Allies advanced from the other direction. Hitler’s refusal to engage in peace talks led to continued conflict until the Soviet forces reached Berlin. Despite suggestions to flee, Hitler chose to remain in Berlin, committing suicide on April 30, 1945, alongside Eva Braun, his long-term mistress and brief wife, in his Führerbunker. Their bodies were quickly burned, symbolizing the final collapse of the Nazi regime. Post-war investigations, including the analysis of a skull fragment in Moscow, confirmed Hitler’s death, closing the chapter on one of history’s most tyrannical leaders.

Legacy

In his will, Hitler dismissed the other Nazi leaders and appointed Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz as the new President of Germany and Goebbels as the new Chancellor of Germany. However, Goebbels and his entire family committed suicide on May 1, 1945. On May 8, 1945, Germany surrendered unconditionally. Hitler’s proclaimed “Thousand Year Reich” had lasted 12 years.

Since the defeat of Germany in World War II, Hitler, the Nazi Party and the results of Nazism have been regarded in much of the world as synonymous with evil. Historical and cultural portrayals of Hitler in the west are almost uniformly negative. This negative view is shared by most, but not all present-day Germans. For example, Hitler’s Mein Kampf is not widely available in Germany.

Despite this, there have been instances of public figures referring to his legacy in neutral or even favorable terms — particularly in South America, the Islamic World, and parts of Asia. Future Egyptian President Anwar Sadat wrote favorably of Hitler in 1953. Bal Thackeray, leader of the right-wing Shiv Sena party in the Indian state of Maharashtra, declared in 1995 that he was an admirer of Hitler.

Two separate religious identities flourished under Nazism. The first was a devotion to Hitler himself. In some cases this resulted in a form of Christianity known as German Christian. The ultra nationalist German Christian churches the movement sought to recreate Christianity replacing Jesus with Hitler, or at least make him a modern day prophet.

For example a common Nazi song replaced the words to the German carol Silent Night with the following lyrics:

“Silent night! Holy night!

All is calm, and all is bright

Only the Chancellor steadfast in fight

Watches o’er Germany by day and by night

Always caring for us.

Silent night! Holy night!

All is calm, and all is bright

Adolf Hitler is Germany’s wealth

Brings us greatness, favor and health

Oh give us Germans all power!”

In less nationalistic churches the German Christian movement passed restrictions allowing only German membership in the Church.

However, the dominant religion among Nazi Leaders was a form of mysticism around nature, the German “Volk” Folk and nature. This belief was strong in groups like the SS and SA. However, Hitler, Himmler, and Goebbels, having been brought up in fairly devout Catholic households, still retained respect for the Church, hence the concordant with Rome.

Hitler during his rule made many steps to restrict Christianity and remove it as a political influence from Germany. The Reich Concordat with the Catholic Church preserved funding and for the Catholic Church but at the cost of making the Catholic Church subservient to the Nazi Party. After a failed assassination on Hitler’s life in 1943 which involved elements of the Confessing Church, (a protestant organization), Hitler ordered the arrest of Protestant, mainly Lutheran clergy. Catholic clergy was also suppressed if they spoke out against the regime.

Hitler often adopted elements of Christian theology in his speeches.

While some Revisionist historians point out that Hitler’s attempt to improve the economic and political standing and conditions of his people and how he went about it was, in essence, no different than that of many other leaders in history, his legacy, as interpreted by most historians, has caused him to be one of the most reviled men in history.

Medical Health

Adolf Hitler’s health has been a topic of considerable debate and speculation, reflecting a wide range of medical issues that he reportedly suffered from throughout his life. These issues have become a focal point for historians and medical professionals attempting to understand the dictator’s physical and psychological state during his reign.

Early Health and Medical Care

Hitler’s health care was primarily managed by Dr. Karl Brandt, an SS officer and surgeon, from the early 1930s, and later by Professor Theodore Morell, whom Hitler met in the late 1930s. Morell, who became Hitler’s favorite physician, was a controversial figure, known for his unconventional treatments. Initially, Hitler consulted Morell for severe gastro-intestinal issues, which resulted in significant discomfort and flatulence, and skin lesions on his thighs.

Development of Further Health Issues

Under Morell’s care, Hitler’s health problems expanded to include an irregular heartbeat and tremors, predominantly on the left side of his body. Morell’s treatment regimen for Hitler included a daily dose of methamphetamines, administered through injections and tablets, which Hitler likely became dependent on, if not addicted to. These treatments, rather than alleviating his conditions, may have contributed to the deterioration of his health over time.

Speculations on Hitler’s Health Conditions

Various theories have been proposed regarding the underlying causes of Hitler’s health issues:

- Syphilis: Hitler’s tremors and irregular heartbeat were speculated to be symptoms of syphilis, a diagnosis that Morell reportedly made by early 1945. Hitler’s extensive discussion of syphilis in Mein Kampf, referring to it as a “Jewish disease,” has led some to speculate that he may have been personally affected by the condition. The symptoms that Hitler displayed, especially in the latter years of his life, are consistent with the tertiary stage of syphilis.

- Parkinson’s Disease: The possibility that Hitler had Parkinson’s disease has also been considered, given the treatments prescribed by Morell in 1945 that are commonly used for Parkinson’s. However, Morell’s reliability as a physician has cast doubt on this diagnosis.

- Other Conditions: Other speculated health issues include irritable bowel syndrome, addiction to methamphetamines, and a missing left testicle—a claim propagated by the Soviet Union following an alleged autopsy, which was later admitted to be fabricated by Lev Bezymenski, the author of the autopsy report.

Conclusion

Adolf Hitler’s medical history remains a subject of intrigue and speculation, with his array of symptoms and conditions suggesting a complex health profile. The reliability of diagnoses and treatments during his lifetime, particularly given the unconventional approach of his personal physician, complicates the effort to understand the impact of his health on his behavior and decision-making as the leader of Nazi Germany. Despite the various theories and speculations, a definitive understanding of Hitler’s medical condition remains elusive, shrouded in the secrecy and propaganda of the era.

Hitler’s family

- Eva Braun, mistress and then wife

- Alois Hitler, father

- Klara Hitler, mother

- Paula Hitler, sister

- Alois Hitler, Jr., half-brother

- Bridget Dowling, sister-in-law

- William Patrick Hitler, nephew

- Angela Hitler Raubal, half-sister

- Geli Raubal, niece and rumoured mistress

- Maria Schicklgruber, grandmother

- Johann Georg Hiedler, presumed grandfather

- Johann von Nepomuk Hiedler, maternal great-grandfather, presumed great uncle and possibly Hitler’s true paternal grandfather